North Brooklyn’s Fight Against A Fracked Gas Pipeline

November 19, 2021

New York claims to lead the nation in clean energy and climate action, but in North Brooklyn, many residents find otherwise.

Neighborhood environmental groups are engaged in a battle against utility company National Grid over a fracked gas pipeline being built from Brownsville to Greenpoint. Critics argue that the pipeline defies environmental protection goals and endangers North Brooklyn neighborhoods, forcing residents, largely communities of color, to pay for a project that will endanger but not service their neighborhoods. National Grid maintains that the pipeline is compliant with regulations. In the midst of a civil rights investigation by the Environmental Protection Agency, the State will decide whether to approve permits for the pipeline’s final stages on December 6, 2021.

If completed, the North Brooklyn Pipeline, officially named the Metropolitan Reliability Project, would be a 30 inch, high-pressure pipeline running for seven miles under Brooklyn streets. Four of five phases of construction have been completed, but National Grid must await a new permit to begin the final phase from Williamsburg to Greenpoint. Carrying natural gas fracked from Pennsylvania shale, the pipeline would not provide gas to North Brooklyn neighborhoods, but instead act as a transmission line to Long Island and Massachusetts. National Grid is also seeking to expand their Liquified Natural Gas (LNG) facility in Greenpoint with two new vaporizers, replacing older models that National Grid claims are less efficient.

National Grid, who did not respond for comment, has stated previously that the project “prioritiz[es] energy affordability” and improves safety and reliability. Christopher Connelly, vice president of gas operations, said at an online information session in October that the new vaporizers would be necessary to minimize outages during cold months. National Grid emphasizes that the vaporizers run only a few times a year, when low temperatures create increased demand.

These reassurances ring hollow with residents living near the pipeline route, many of whom already experience health problems caused by existing pollution. Brownsville already has the highest asthma rates in Brooklyn due to unsafe housing. In Greenpoint, a longtime industrial zone that already borders a Federal Superfund Site, children are four times more likely to have lead poisoning than in other NYC neighborhoods.

Anna Tsomo, an organizer working with the No North Brooklyn Pipeline campaign, became involved when she found out that the pipeline route was one block away from her mother’s home in Brownsville.

“It really goes through predominantly Black and Brown and working class communities,” she said. “This kind of toxic infrastructure is very rarely built in wealthy and whiter communities. Class and race correlate to chronic illness, and it’s because toxic things are built in communities where there’s also lack of access to health care. It’s environmental racism.”

In early November, the EPA announced it would investigate the Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC) and Department of Public Service (DPS)’s actions in approving the pipeline, after several neighborhood groups filed a lawsuit against National Grid. The plaintiffs, Brownsville Green Justice, Ocean Hill-Brownsville Coalition of Young Professionals, Mi Casa Resiste, and the Indigenous Kinship Collective, argue that National Grid rushed through the community review process and purposefully routed the pipeline through communities of color.

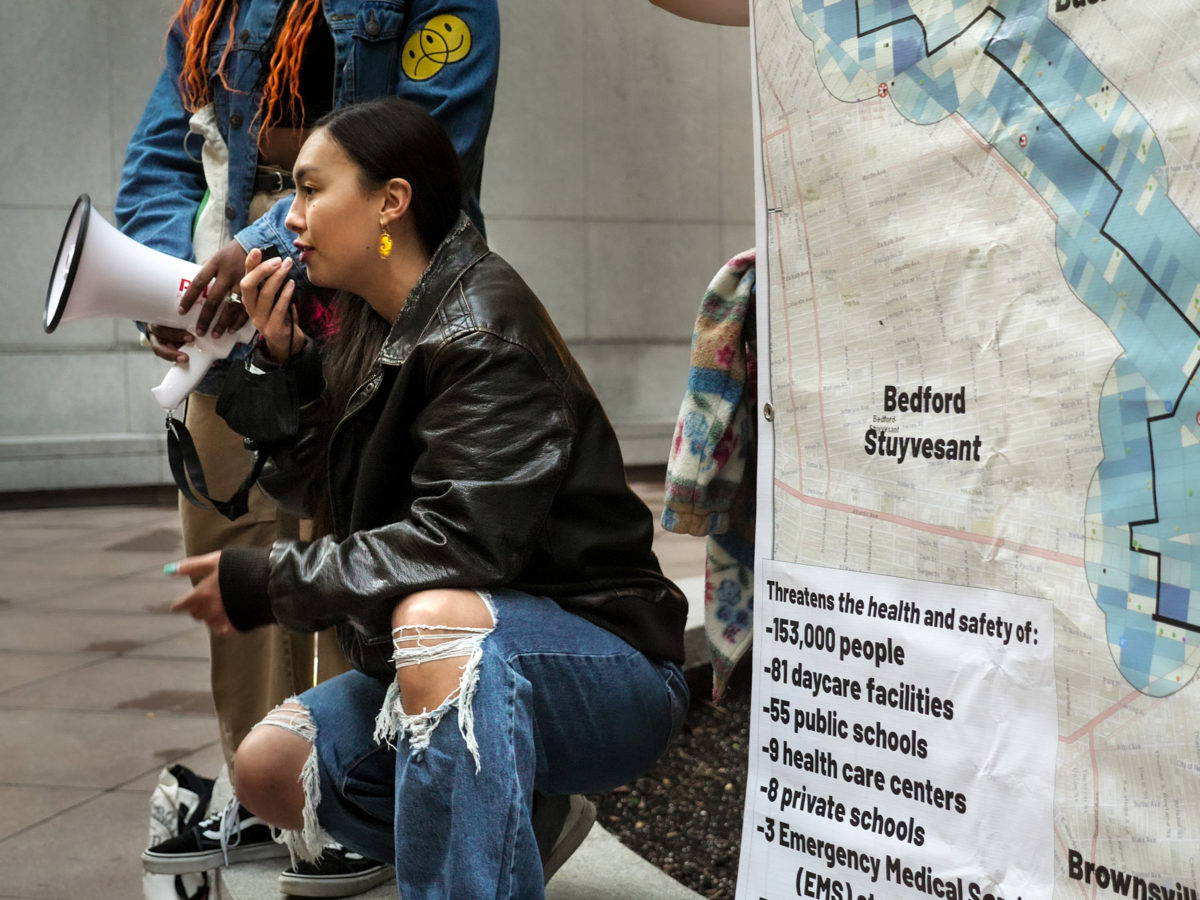

Tsomo points to a map, explaining that 153,000 people live in what could be an evacuation zone if an explosion or other accident were to occur along the pipeline, along with 89 schools, 81 childcare facilities, and nine healthcare centers In the last ten years in the United States, there have been 6,950 reported pipeline accidents, an average of 1.7 per day, resulting in 156 deaths and 688 injuries, according to FracTracker. In January 2020, two National Grid workers were seriously burnt by an exploding gas line in Bay Ridge, causing a fire to burn for hours from an underground hole and nearby residents to evacuate.

Tsomo and others in her coalition have organized a gas bill strike against National Grid to protest the pipeline and associated rate hikes. Hanging informational postcards from the doorknobs of buildings along the pipeline route, textbanking, and holding educational events each week, they encourage National Grid customers to keep a balance of $66 dollars, the average rate hike per customer per year to pay for the pipeline.

“There’s power in refusing to pay for our own poison,” said Lee Ziesche, the community outreach coordinator for grassroots activist group Sane Energy Project.

For Kim Fraczek, director of Sane Energy Project, what lies at the heart of the situation is a longstanding strategy of misinformation about natural gas. Raised in Pennsylvania, she grew up next to a reservoir that is now contaminated by fracking, making her family’s water undrinkable. Fracking, the process of drilling deep underground to gas-rich shale rock and pumping a high pressure mixture of water, sand and chemicals to fracture the rock and draw out gas, has been banned in New York since 2014. However, companies like Natural Grid can continue to pump in fracked gas from other states.

Fraczek emphasizes that even the term “natural gas” has been utilized by gas companies to control their public image. In a study at Yale University, researchers compared respondents’ reactions to the terms “natural gas” and “methane gas,” the greenhouse gas that comprises 70-90% of natural gas. While negatively associating methane gas with climate change, respondents generally believed that natural gas was less harmful to human health than other fossil fuels.

A gas vent flares beside a LNG storage tank in National Grid’s Greenpoint facility. Brooklyn, NY, 2021.

Photo by Will Landis-Croft.

Fraczek led interested residents on a tour of the area surrounding National Grid’s Greenpoint LNG facility in mid-November. Behind tall fences, stacks reach into the clear night sky and illuminate it intermittently with flames. When Fraczek explained that these flames were the result of burning excess methane, Mitch J, a longtime Greenpoint resident and gas bill striker, was shocked. Flaring, as the practice is called in the industry, was once limited under the Obama administration because of its major contributions to climate change.

“I can see that in the back window of my apartment,” Mitch said. “It’s flaring more often than not.”

Guiding the group to a field on the corner of National Grid’s property, she points past the barbed wire fence to a sign that reads “Welcome to Greenpoint Little League Field,” with the National Grid logo displayed beside it. A blank scoreboard looms over neatly cut grass and empty bleachers. After soil sampling in 2010 revealed the presence of dangerous chemicals left over from industrial activity, National Grid decided to suspend the field’s use.

“This field was constructed as a way to say, ‘We’re good community neighbors,’” explained Fraczek, “Guys come in here and trim the grass, but no child or adult can play here because the ground is so toxic.”

Fraczek promotes the building of community-owned geothermal exchanges, wind farms, and solar projects, which could be constructed by the same workers hired to build pipelines. “But that doesn’t make money for John Pettigrew,” she said, in reference to the CEO of National Grid.

Still, she believes that the fight against the pipeline can be won. Recalling the successful fight against a proposed LNG plant off of Rockaway Beach, she said, “We organized for three years against that project, and now we’re building an offshore wind farm that will be online in 2022. Our fights see really tangible wins.”